The political class bought the silence of the working class with redundancy and early-retirement packages, and then, with their tacit complicity, embarked on technological upgrades that were nothing but old equipment sold off, given a fresh coat of paint, and then bought back at an exorbitant price. They continued by selling for scrap the country’s major industrial plants and then the land they once stood on. After which they embezzled the budget through rigged tenders that virtually bankrupted the country.

They blocked Romania’s entry into the E.U. and N.A.T.O. as long as they could. They blocked development of the country’s infrastructure. They systematically wrecked the health, education and judicial systems. In the courts they blocked restitution of private property confiscated by the communist régime so that they could buy it up for derisory sums. They sold off resources from petrol to forests at knock-down prices.

They infested the whole of the country’s central and local administrations with their relatives. They created a system in which the political class was made up mostly of people without an education, some of them even illiterate, but who were prepared, for want of any other opportunities, to compromise themselves by stealing for the Securitate apparatus that had ruled Romania for seventy-five years.

All the while, the Securitate apparatus variously have placed the blame for this unimaginable disaster on democracy, the Americans, Merkel, the E.U. Băsescu, Soros, Iohannis, multinationals.

I remember the timid attempt at a protest made by History students in 2011. As it happens, I was the only journalist there to document that unhoped-for moment of awareness. The young protesters were so cowed that they wanted me to ask permission to photograph them, saying that the dean of the faculty had banned the press from being there. This despite the fact that one of their demands, which they had chalked up on the blackboard of the lecture theatre, was that the dean be sacked. The protest fizzled out almost immediately, although it did place on the agenda the Spiritual Militia protests led by Mihai Bumbeș.

Then came the U.S.L. attempted coup in 2012. The entire party apparatus was unable to muster more than eight thousand people for its rally at the Triumphal Arch, of which around three thousand then proceeded to University Square to provoke street fighting. The victims of the coup ought to have led to the fall of the government and the sacking of the president. I couldn’t help but notice that at the time civil society didn’t lift a finger to protect democracy. We were still paralysed with fear.

Then came the Roșia Montană and Colectiv protests. These two protests were crucial in restoring people’s courage to protest, since both resulted in seeming victories.

After unexpected defeat in the presidential elections of 2014, the P.S.D. mobilised themselves and repainted an ageing, impoverished, poorly educated Romania red once more.

Arrogance founded on election results and the pressure of all the crooks in politics and government made the P.S.D. try to become a force partly independent of the old secret police, not because they had divergent interests regarding the good of the country but because they believed that the slaves could become masters too.

Pushed from behind by the crooks who wanted to get out of prison and by those who didn’t want to end up there, the P.S.D. began to make a series of fatal mistakes, whose culmination, unfortunately for them, were the biggest protests since December 1989. After 2012, this was the second violent attack against Romania’s democracy, two reckless and criminal attempts to endanger our country’s European course.

The first of the mistakes was to put the former secret police on the public agenda. In an orchestrated and forceful way, for the first time the television channels identified the former Securitate men as the source of all evil in Romania. The Securitate, the same as the mafia, like a life of crime, but they don’t like being in the spotlight.

Problems with the law prevented Dragnea from becoming prime-minister. Since he couldn’t be the official boss, he put a pathetic puppet in his place, hoping that nobody would cotton on to who was really running the government.

He then proceeded to amnesty and pardon the corrupt politicians who had been put in jail, a plan that had been ready since 2014, but which was thrown into disarray when Iohannis won the presidential election. This decision, along with a plan in effect to decriminalise thievery in Romania, made people take to the streets.

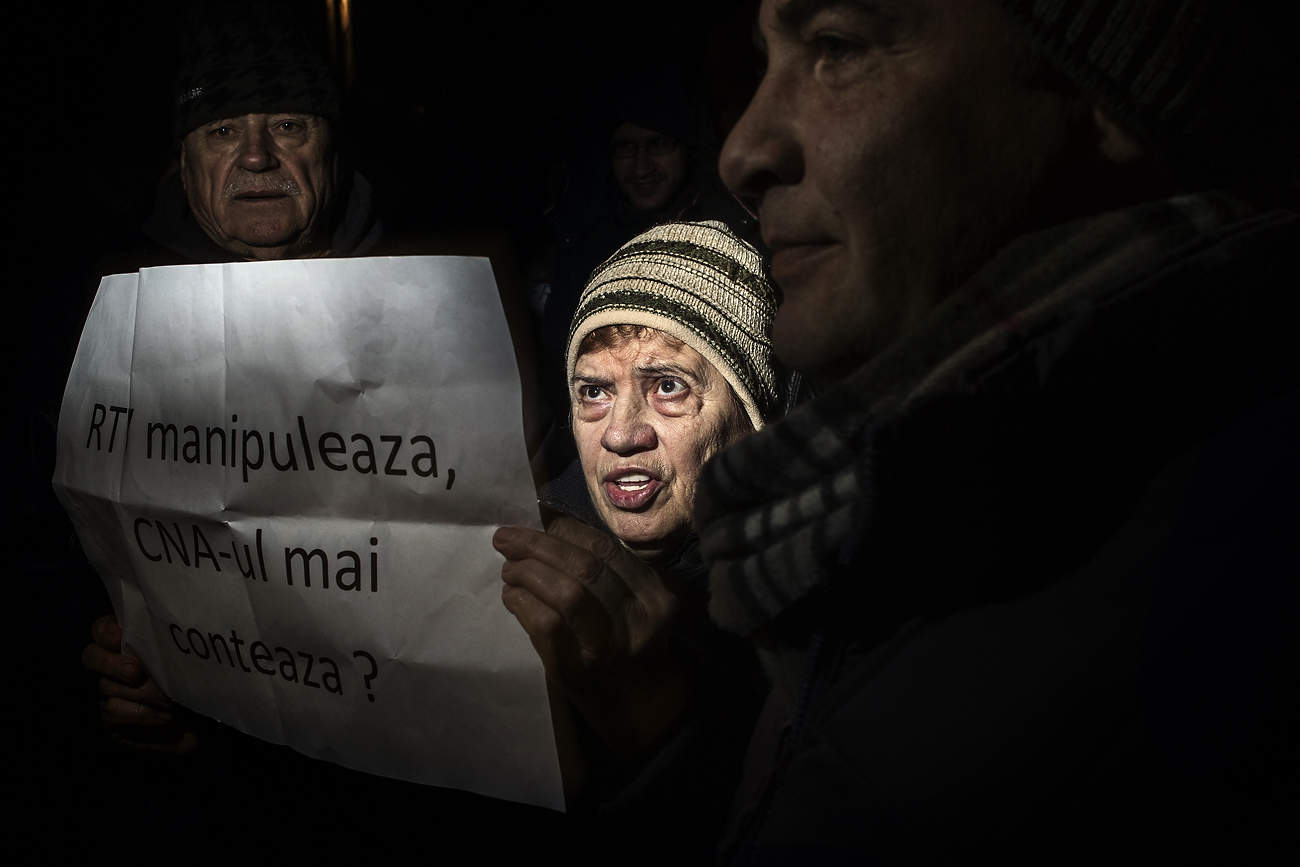

There was talk of manipulation, as if manipulation wasn’t part of the game. There was talk of children being present at the protests, as if their future wasn’t at stake. There was talk about the protesters’ social and financial position, as if there were social classes excluded from the game. It ended up in an antidemocratic, anti-European, anti-values discourse, going so far as the attempt to incriminate multinationals for their supposed support of the protests, as if multinationals weren’t also victims of the same obtuse, abusive, crypto-communist system.

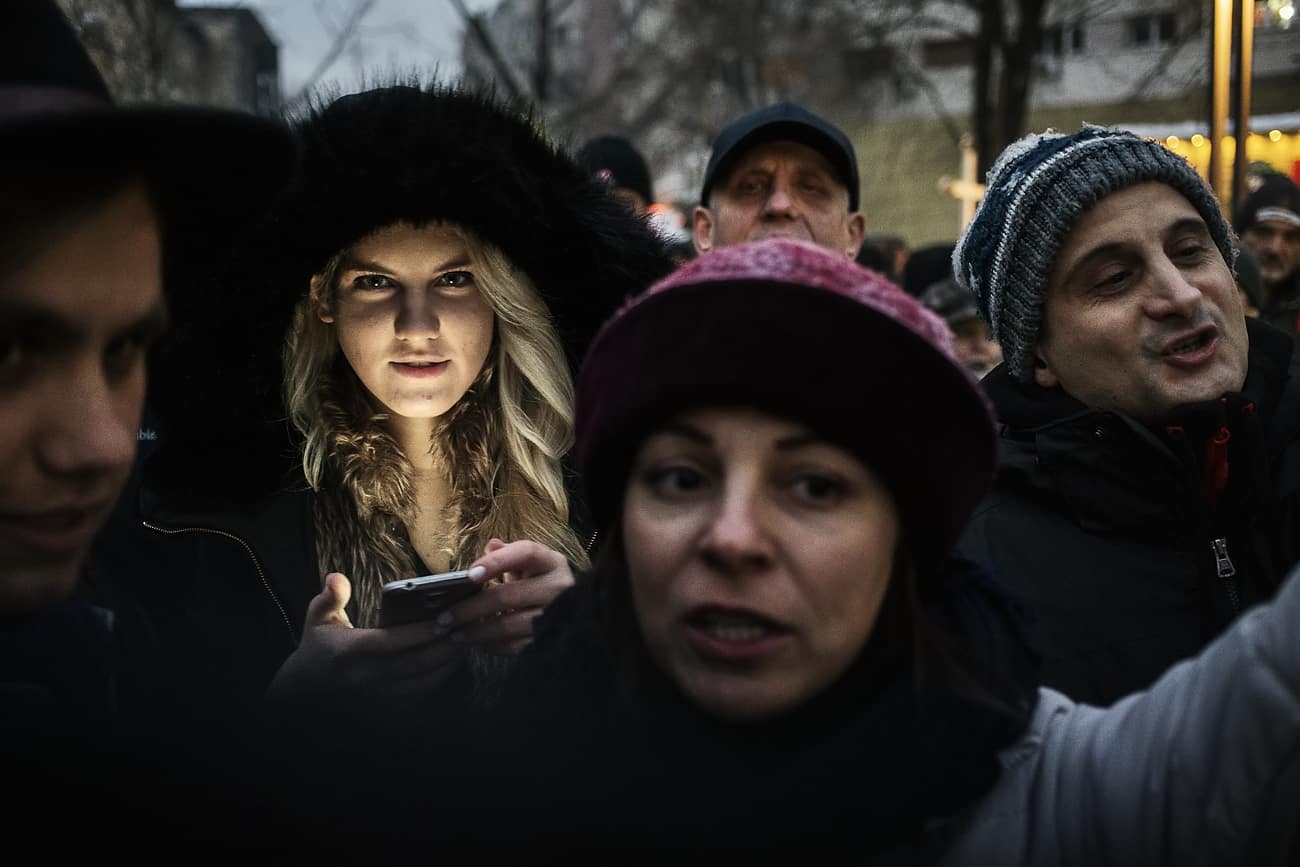

I attended the protests every day to get a feel for what was taking place and to meet the protesters. For me, both those who protested peacefully and those who fought the forces of law and order had their merits. So too did those who protected the institutions of state, who, with minor exceptions, did their job professionally. A strong civil society ought equally to be able to cast ideas and rocks.

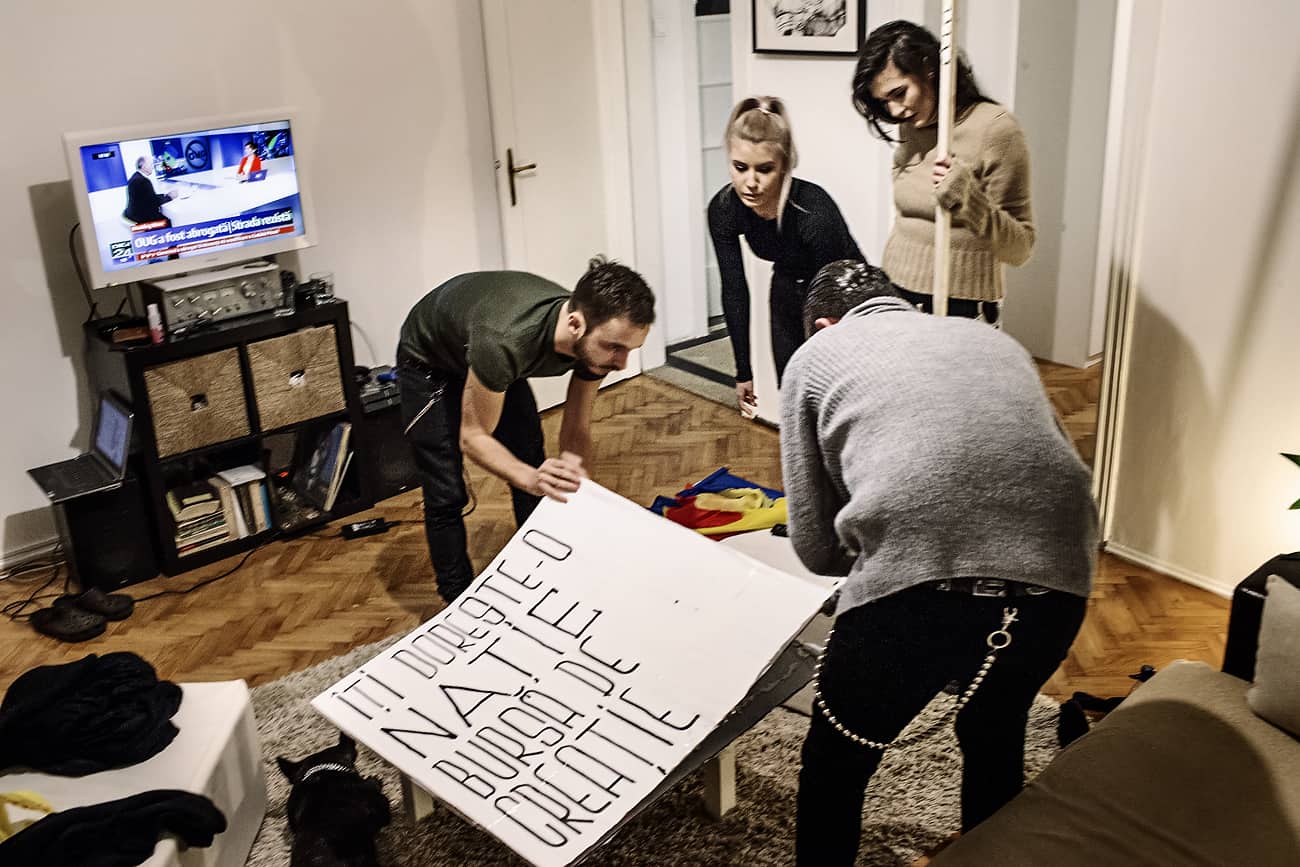

This was how I came to meet the four musketeers: Florina, Maria, David, si Bobo. The first three lived together in a rented flat near Hala Traian. As soon as I entered their flat, I felt like I had walked onto the set of Friends.

Florina is a medical student. Her bedroom was next to the hall. Quiet and seemingly shy, Deni has a delicacy that can captivate you. Her strength is in her eyes, in the way in which she watches you silently.

‘My going out to demonstrate was motivated by a simple game of the imagination in which I put myself both in the immediate future and the more distant future in which I saw my children already grown up. Although my medical career was mapped out as soon as I was admitted to medical school, only now, in a short while, will I genuinely be part of the medical system. And I see myself there, integrated in this system which unfortunately doesn’t at all work the way it ought to. My big dream is to be able to live in my own country at peace, fulfilled, and appreciated after so many years of schooling. The sense of belonging to my country is present and intense and I wouldn’t want to leave my country, the way many medics do nowadays, unfortunately. I want to succeed here, I want to work in an environment in which patients can arrive confident that they will be treated as such and know that they won’t leave hospital sicker than when they came because of nosocomial infections. I want to work in a system in which I’m not ashamed to look the patient in the eye when I tell him that in order to operate he’ll have to provide the necessary materials, from the sterile pads and stitches to medicaments. I know that all this could stop if the money allocated to the system really reached the hospitals and they didn’t play at thieving. At the same time, I’d like to be paid appropriately for the effort I make, and if this happened, then it would certainly spare us having to make big and small plans to work elsewhere, having to chase around after money, just because the money paid by the hospital isn’t enough for a decent living. And yes, I went out to demonstrate because I can’t support the continuing theft and the bad way things are run in this country and because I believe in change, I believe that one day competent people will be in charge and get things back to normal.”

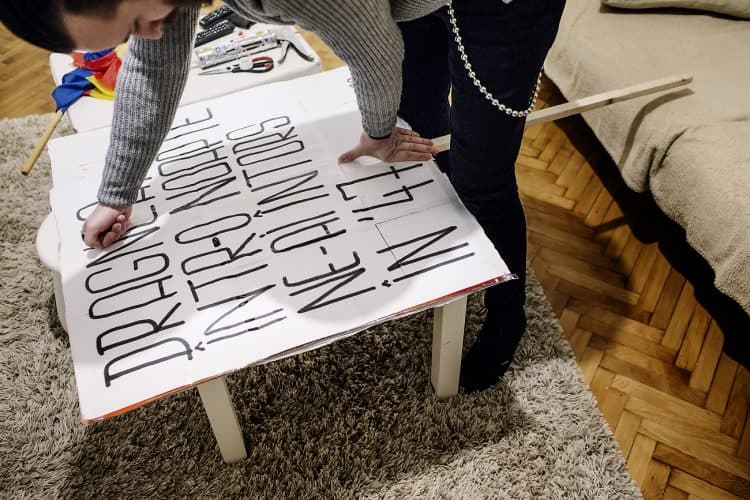

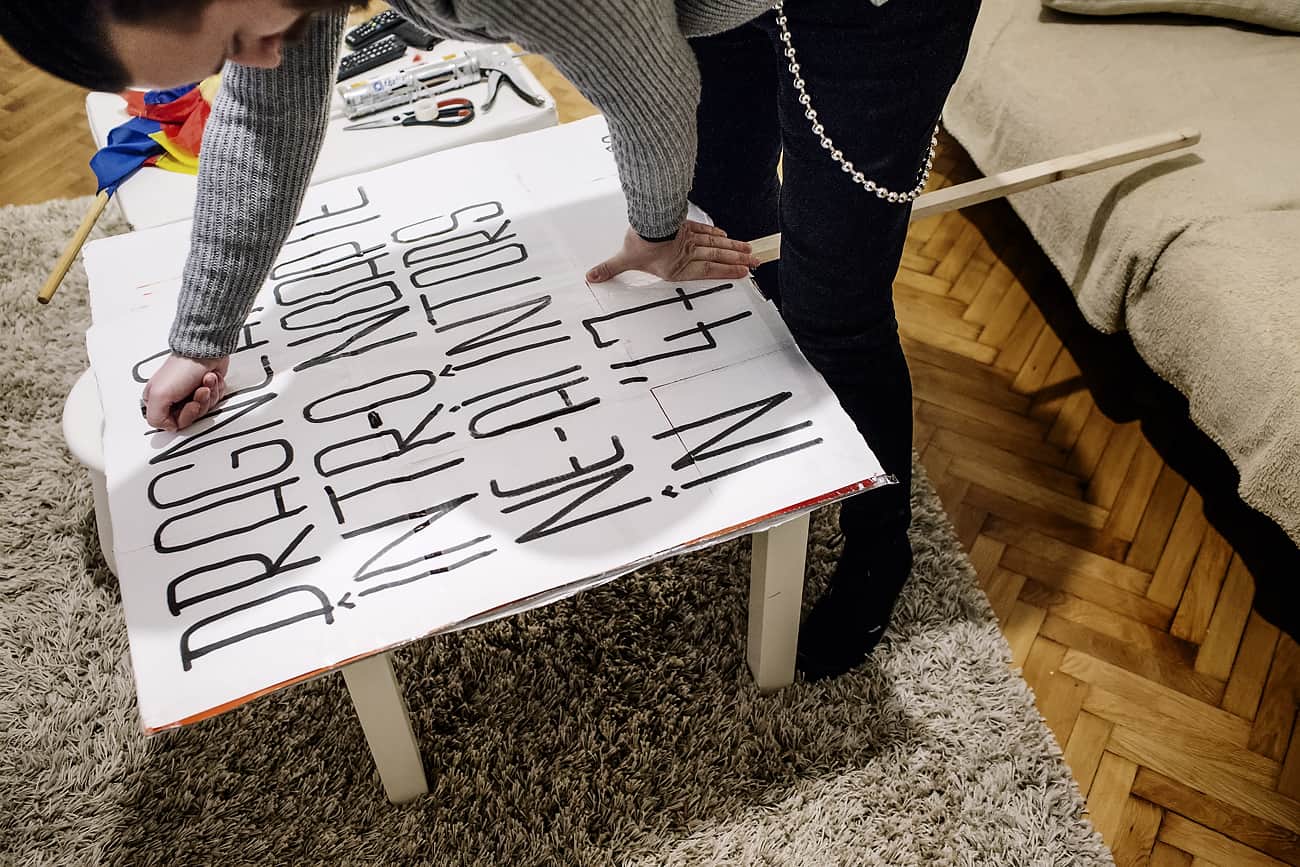

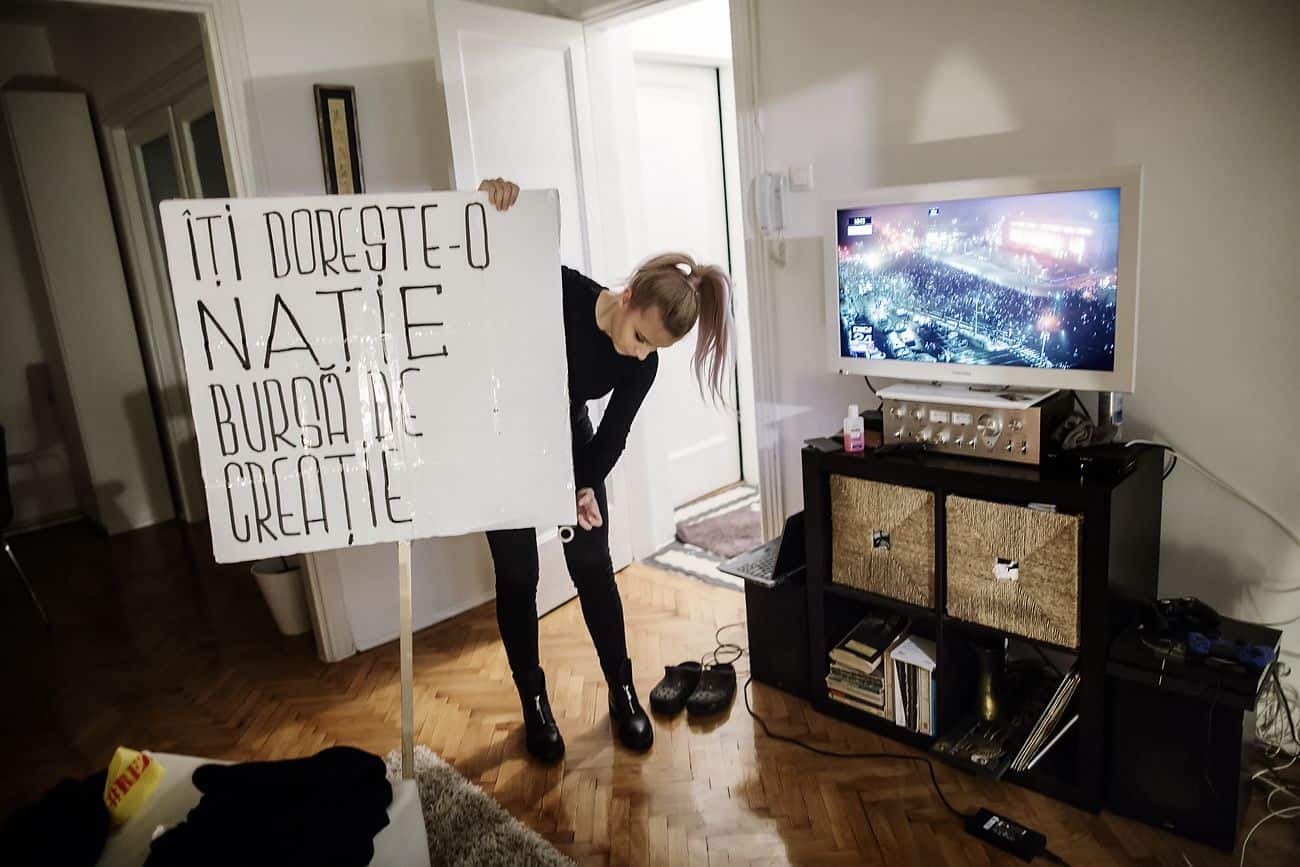

Maria is aiming for a career as a magistrate. You can’t walk past her without noticing the positive, unifying energy that animates her. The compassion that is part of her nature gives me hope in the future: at least those who enter her court will be guaranteed justice in its purest and noblest form. Maria is directly responsible for the subtlety of the message on the placard they’ve prepared for the protests: ‘You want an arts grant nation’ and, on the other side, next to her father, ‘Dragnea, in a single night you took us back to ’47’.

David, aged twenty-eight, is the epitome of the young man who has a complex range of experiences, from football to galleries and climbing the multinational corporate ladder. These experiences make him highly protective of those around him. He and Maria are two extremely strong entities, but through their relationship as a couple each potentiates the other.

‘If I were able to imagine myself demonstrating to a soundtrack, then the song would be “Patria” by Daniel Iancu. I demonstrate because I want the words of his song not to end up becoming a prophecy fulfilled. I believe that we young people are society’s most responsible conscience, maybe only because right now we have the most time on her hands to rectify the things that are wrong and which damage and will continue to damage this country in the medium and long term. We are the ones who perhaps have the biggest responsibility to rid society of its biggest enemy. Which is indifference, and with it also came the insane lethargy in which we wallowed. Maybe it took us a long time, maybe it took twenty-six years of suffering, but I read somewhere that suffering polishes character and personality. Maybe only now is the polishing complete and our characters are represented in the best way and we’re able to fight for what we want from Romania. The demonstrations support this argument, they’re demonstrations of beautiful people from a number of viewpoints. We’ve reached the moment when we are perhaps trying to build a different kind of identity for this nation, namely one that reacts to every injustice and which demands the right to be respected by elected officials and others. It’s not at all late to do this, in the end, for so many centuries we were caught between empires and our periods of freedom have been so brief. We want to be the ones who abandon Romanian proverbs such as “The sword does not cut off the bowed head.” I demonstrate for truth, justice, probity. I demonstrate for my country and its good, I demonstrate for my family and for my future children. I demonstrate for myself, for the ones at home and for the ones at my side.’

‘The political class gives us no respect and don’t even do their jobs for us. The national interest has become their personal interest. Someone who looks only at surfaces, at the superficial level, would say that those lads don’t have any plan to do anything constructive. But if that some someone went further than surfaces, if he did the research, went deeper, he’d be shocked at what he discovered. He’d realise how much we’d lost in twenty-six years, he’d realise, for example, that sectors vital for our development, such as health and education, have been destroyed. Perhaps not by accident, because when you have forty per cent of pupils who are illiterate, it means you have forty per cent fewer problems from that particular generation. They don’t provide inspirational models, people whom we can admire for their integrity, loyalty and professionalism. Today, unfortunately, values have been inverted. The normal has become abnormal, and the abnormal normal. We only have to look at some of those in key positions to understand that this is the way it is.’

David hopes Romania will be able to rebuild its hierarchy of values at every level, the values vital for the country’s future, and to protects its old folk, young people, and resources. Not least, he hopes that by the way in which it operates Romania will come to inspire people to work hard and be honest.

Bobo works for an advertising agency. Few people are more suited than he is for work in a client service department. Those who know him probably value him for his openness, friendliness, cheerfulness. What impressed me about him was also the stubbornness with which he held his placard in a strong wind. No matter how hard the wind blew, he didn’t give up.

Bobo demonstrates knowing that although things will be hard to change for the better, he doesn’t want to worry any more about the ways in which they rob us. He feels that the entire political class doesn’t set an example in life for him and don’t help him to love his country and to support and help other Romanians. He dreams of a technologised, digitalised Romania, of a growth in the standard of living to match taxes, and in the future a Romania where will be able to have expectations not just of himself but also of the country.

Andrei, a lean young man a head taller than almost everybody around him, I spotted in the crowd thanks to the tricolour painted on his face. A third-year political sciences student at Bucharest University, Andrei hopes to have a career in the diplomatic service or in politics. We met again in his room at the student hall of residence for a few minutes before he went home to Navodari for the holidays, where his father was waiting for him.

He had taken part in the protests because he thought a government that passed laws that were personalised for party bigwigs and other members of the P.S.D. and A.L.D.E. didn’t represent him.

Andrei thought that right then, the whole of Romania’s political class couldn’t provide prosperity or a vision of the world in which he wanted to live and start a family. That was what made him feel forced to think about emigration.

He wants to live in a country where most of the people are morally upright, a country where the past is respected, a country where people work hard for a better future.

In the 1990s we should have given a million dollars to all the communist bigwigs conditional upon them not getting involved in the political life of the new Romania. We cobbled together a Lustration Law but the ex-Securitate made sure it was never put into practice. The only real demand of a Romania that wants to be free of the past and to have the chance of a genuinely democratic future is a law of Lustration adapted to today’s society. We need a long list of people who should finally be banned from politics and government. They always told you that in politics they sacrifice themselves for the good of the country. Well, the time has come for the country to “thank” them and to exempt them once and for all from the burden. Without creating a breach in the system’s defences, people of merit will never have access.

The mass of demonstrators is a miniature of Romanian society as a whole, with all its good things and bad things, with all its good people and bad people. As long as they include people like Florina, Maria, David, Bobo and Andrei, we still have a chance. Perhaps the final chance. Maybe not us, maybe not them, but certainly our children.

Because if not even now will we be able to solve the issue of the political class, then the only form of peaceful protest I can still think of is for us all to emigrate, regardless of what the rabid nationalist propaganda has drummed into your head.