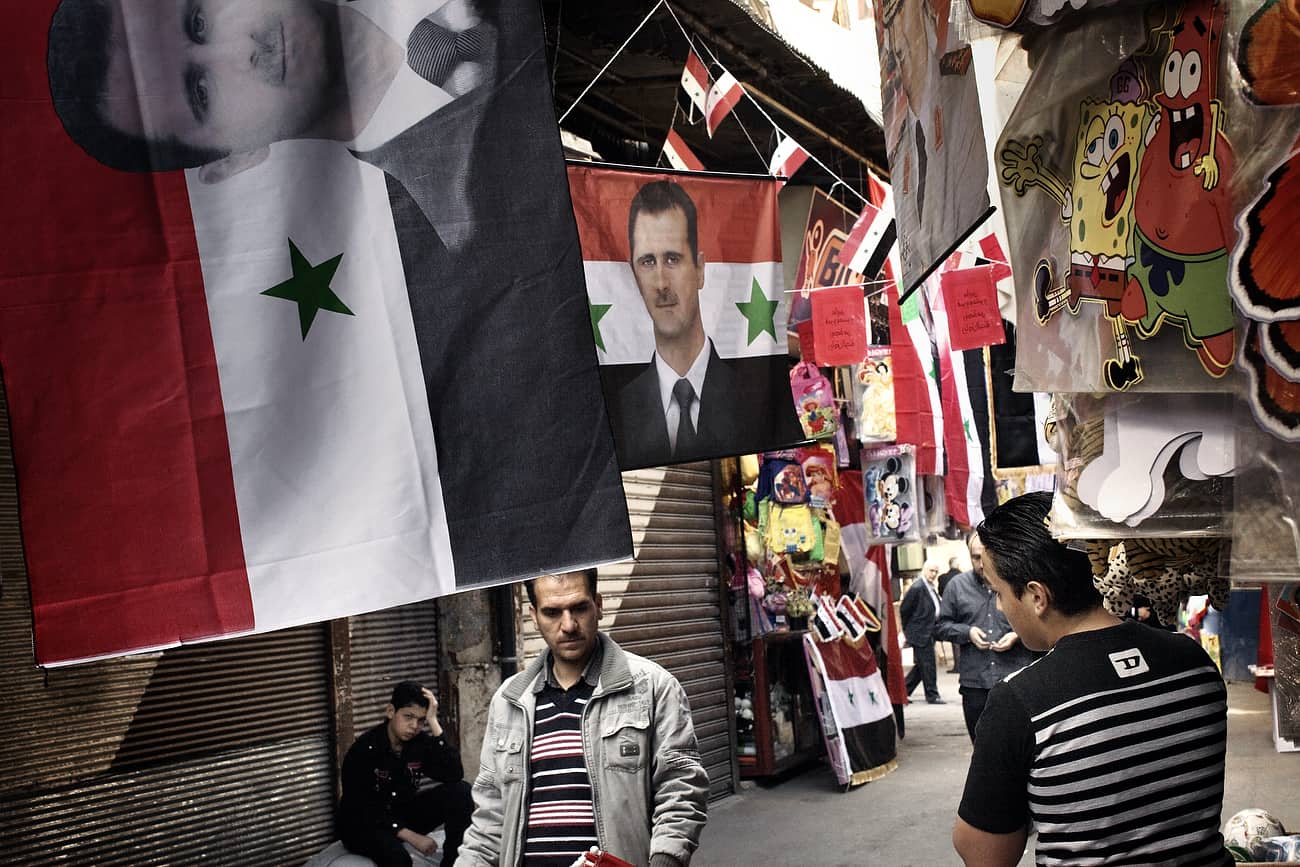

Less than forty-eight hours earlier, in the town of Daraa, south of Damascus, dozens of Syrians had been killed by government forces following a march of protest against the regime. On 23 March demonstrators from the town and the neighbouring villages had entered the town at around five o’clock in the afternoon, after marching for a number of hours.

They were demanding freedom, the rescinding of the emergency law that allowed the military regime to quell all forms of opposition, and the release of political prisoners arrested on the basis of this arbitrary law.

Reaching the town centre, the marchers were met by government forces, which opened fire on them. Two brothers from Al Hrak were shot by snipers, who used a classic ploy: selected at random, the first brother was felled by a bullet in the middle of his forehead, the second brother rushed to help him and was immediately killed, also by a shot to the head.

On the following days I tried to enter Daraa and Assanamein, but both towns were circled by troops. On 26 March I entered the village of Al Hrak. Here, members of the victims’ families and villagers had taken to the streets to demand justice.