At the beginning of the twentieth century, most of the Romanians where peasants, fighting and, a lot of times, dying for a piece of land. My grandfather had four children. Just like him, most of the Romanians had many kids.

If we consider the lack of medication and the effects of both World Wars, we have to admit that we are here today only because our grandparents didn’t stop having kids, and did not resume to just fulfilling their ploughing careers.

The Romanians where indeed peasants but not stupid, so they quickly realized, without the help of any NGO’s that it’s not a bad idea to send the kids to school. But sending kids to school is not an easy job and it doesn’t come cheap. Actually, if you think that many of them had to give up a cow or a piece of land, it was quite expensive. Because it was so expensive, most of them had to evaluate their offsprings and send to school only the smartest of them. The rest had to wait. For many, their turn never came.

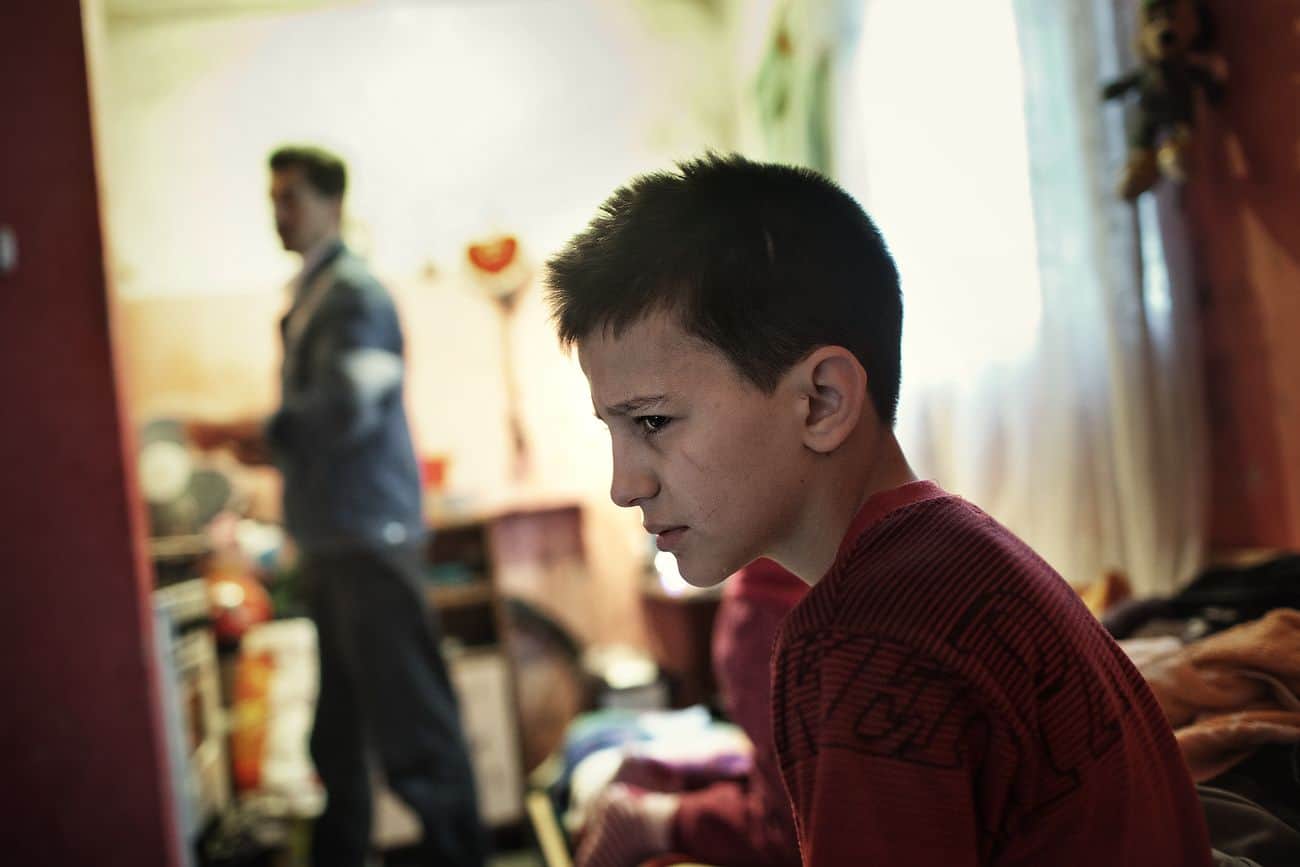

Now, one hundred years later, all sorts of NGO’s and international organizations, on a patronizing tone, preach about the importance of schooling to Romanians living below poverty line. Many of these Romanians are of Romani origin. Like our grandparents, Romani today are the only citizens in this country with many kids, sometimes five, eight or even more.

Most of these NGO’s representatives, with their full bellies and their squeamish nature to the sight of the poor conditions these people live in, spend just a few minutes passing down their wisdom and then they move on.

According to them, if you tell someone unemployed, hungry, without running water or electricity to send their eight children to school, you’ve done God’s work on this Earth and you can go home and be proud till you burst.

It puzzles me how we can’t learn from our past. Millions of Romanians don’t have theproper conditions to send one kid to school, not to mention eight. Unlike one hundred years ago, these people have nothing to sell, but more importantly the discrimination makes it impossible for many of them to find a decent job. Therefore, marginalization took an extreme toll on them and miss-shaped their life expectations.

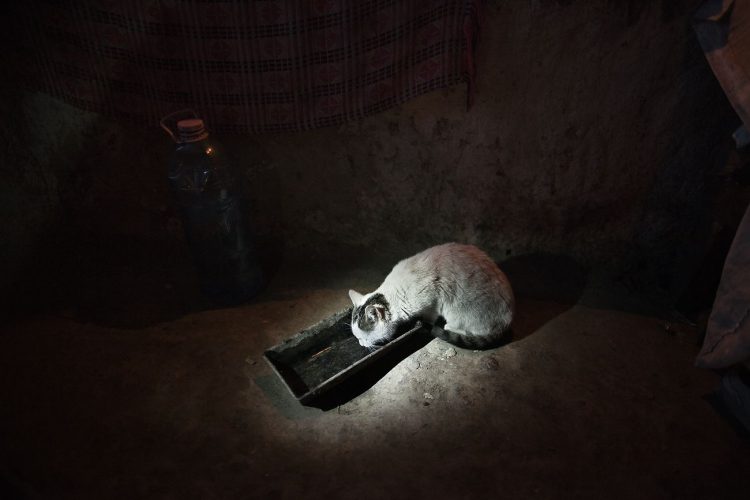

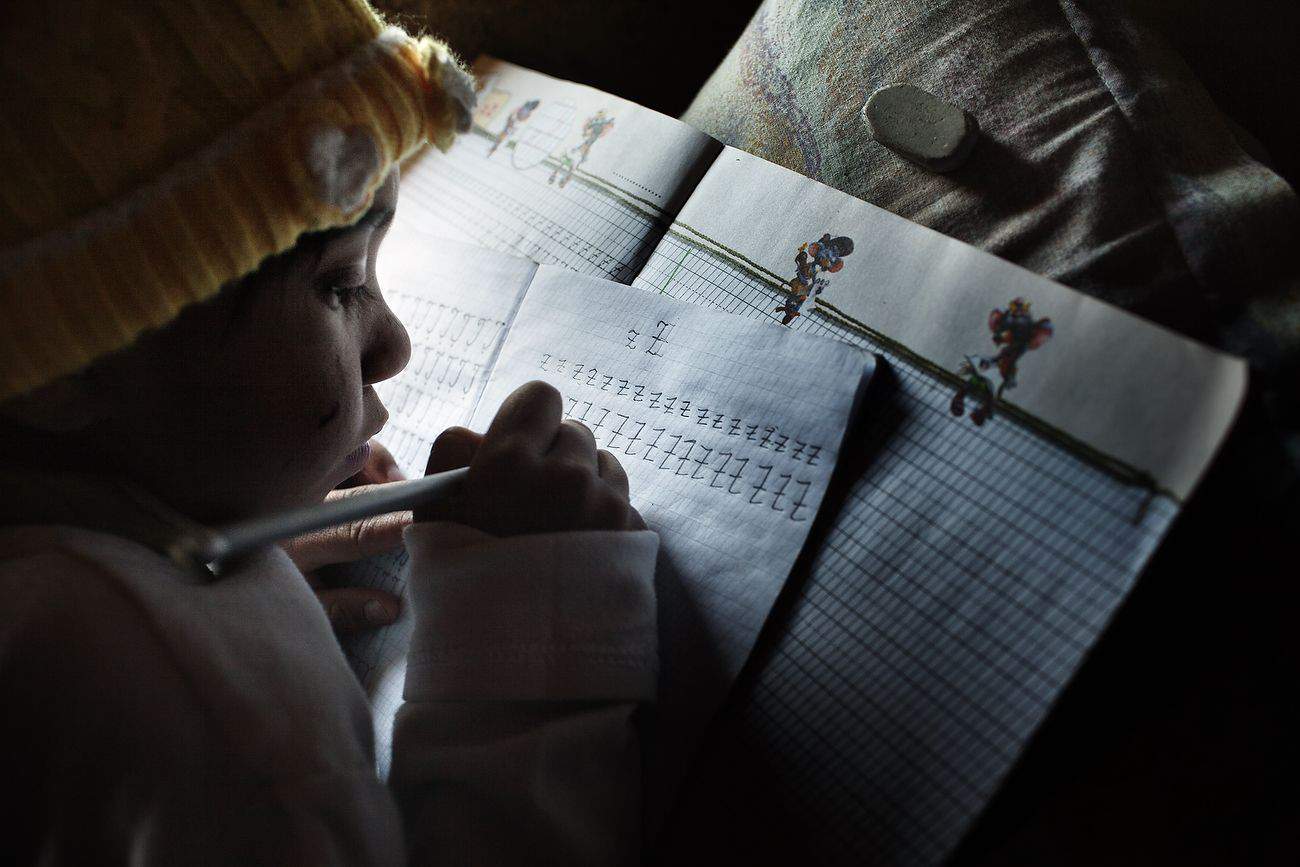

When I look at Canuta’s kids going to school regularly it fills my heart with joy. For I know that we only need twenty years to change the destiny of this country for the better. When I know they go to school in the same clothes they slept in, it blows me away.

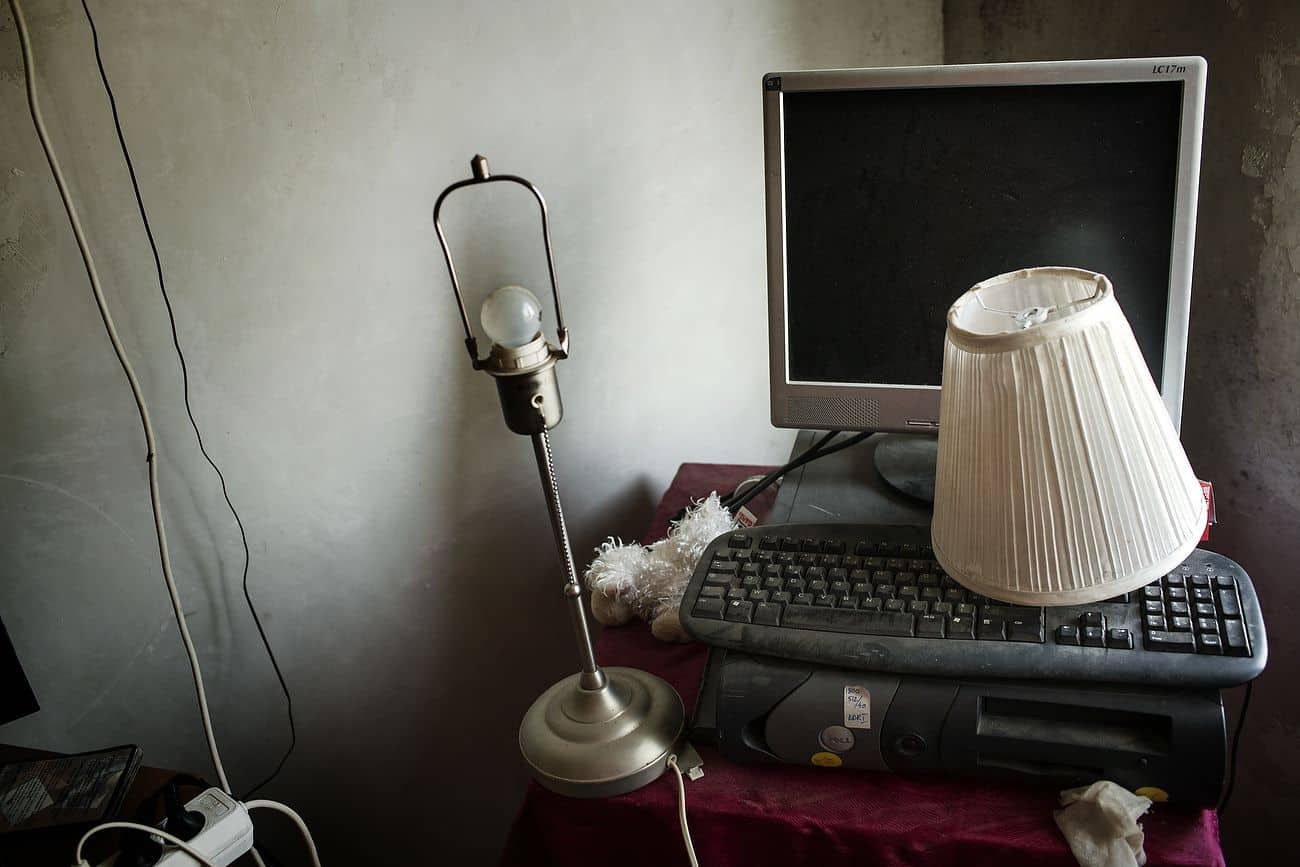

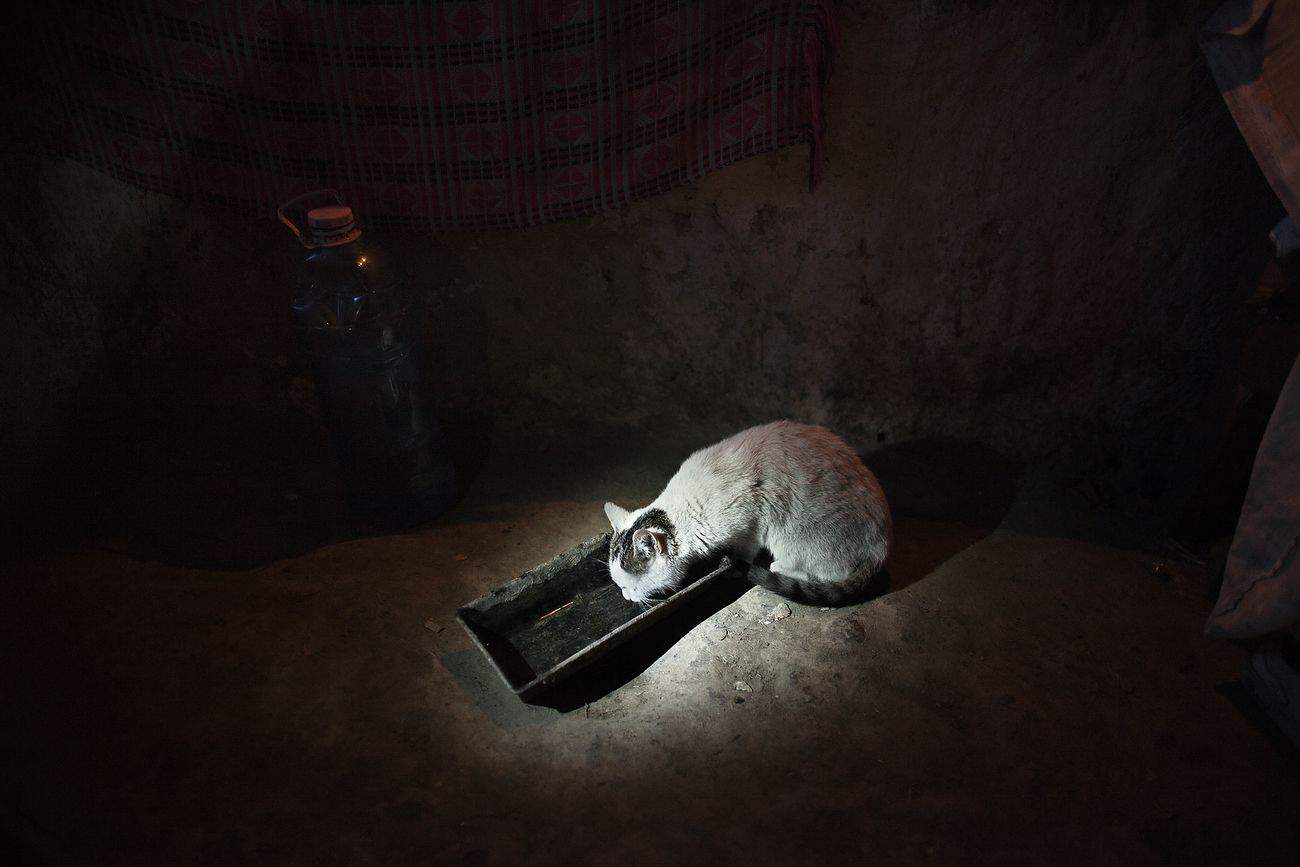

Without running water they bath now and then. In the winter they can’t read after four in the afternoon. To them, breakfast holds almost no meaning. Unless they have some leftovers from the night before or if you count the milk and the bread they get at school.