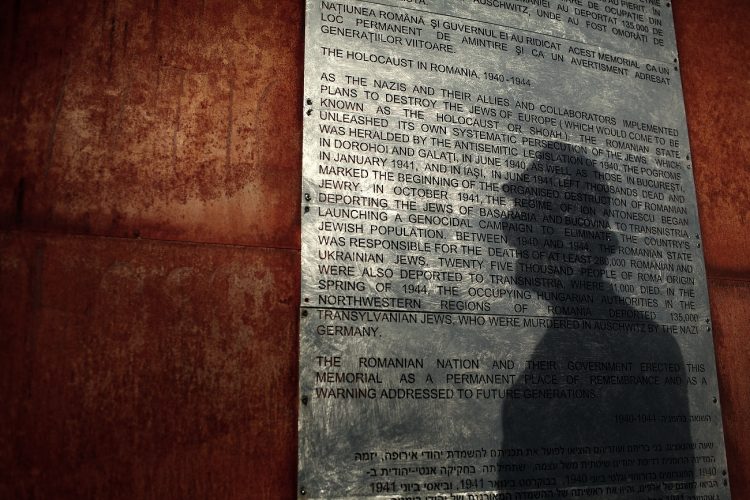

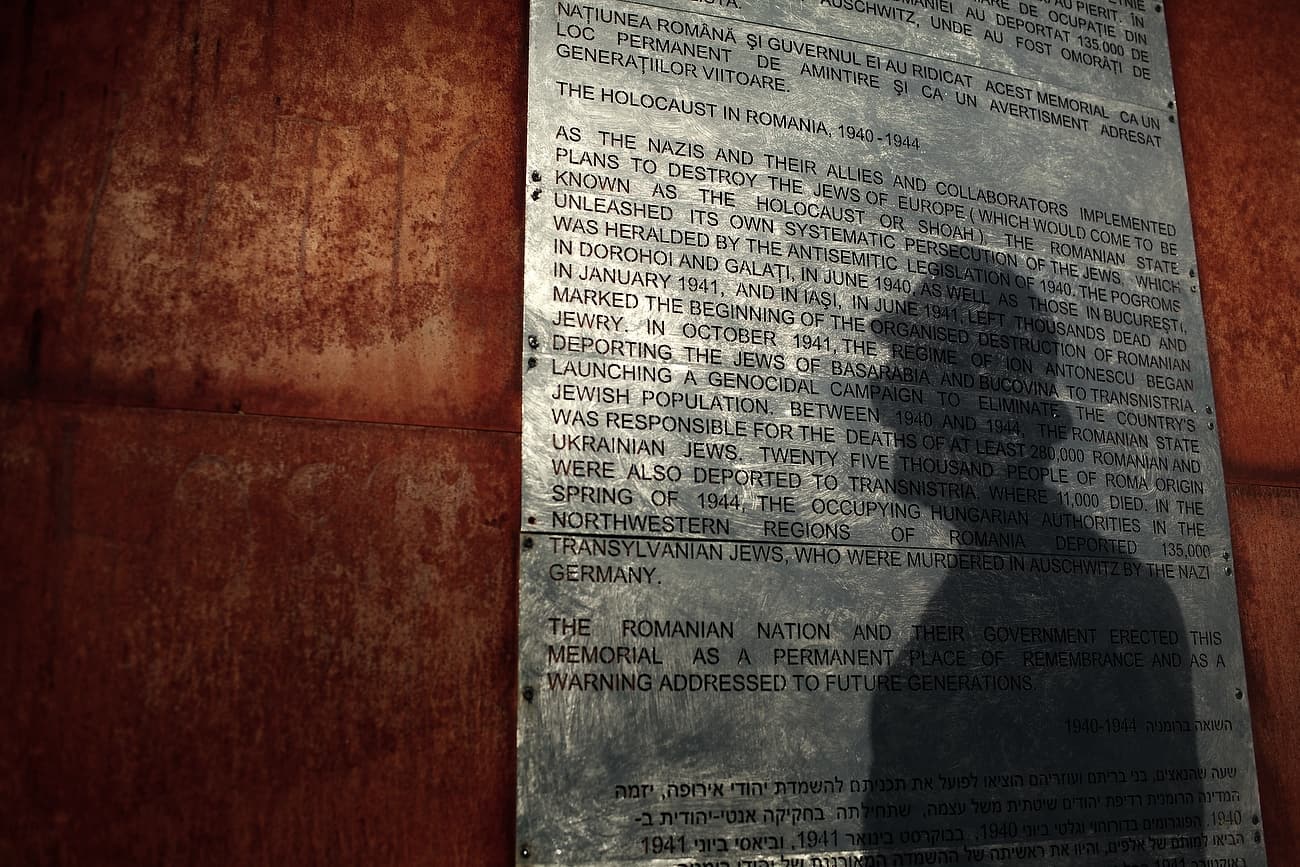

Many documentaries have been made about the Holocaust. Seventy-five years later, the greater part of the Romanian population still believes that we did not kill any Jews, let alone that we were second only to Nazi Germany in the number that were killed.

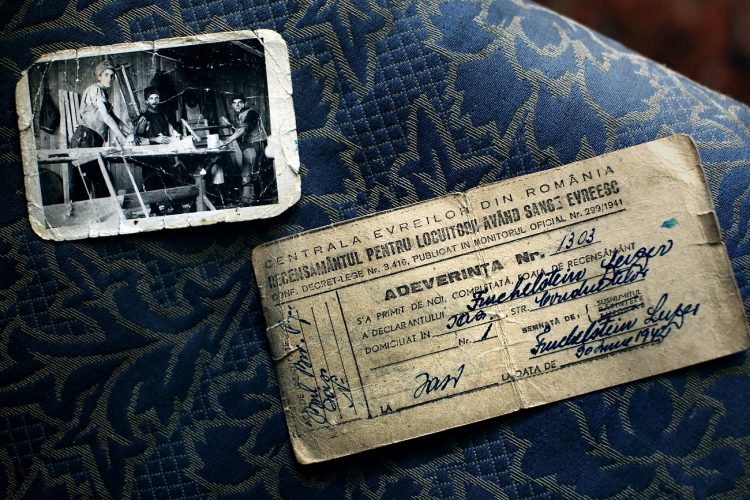

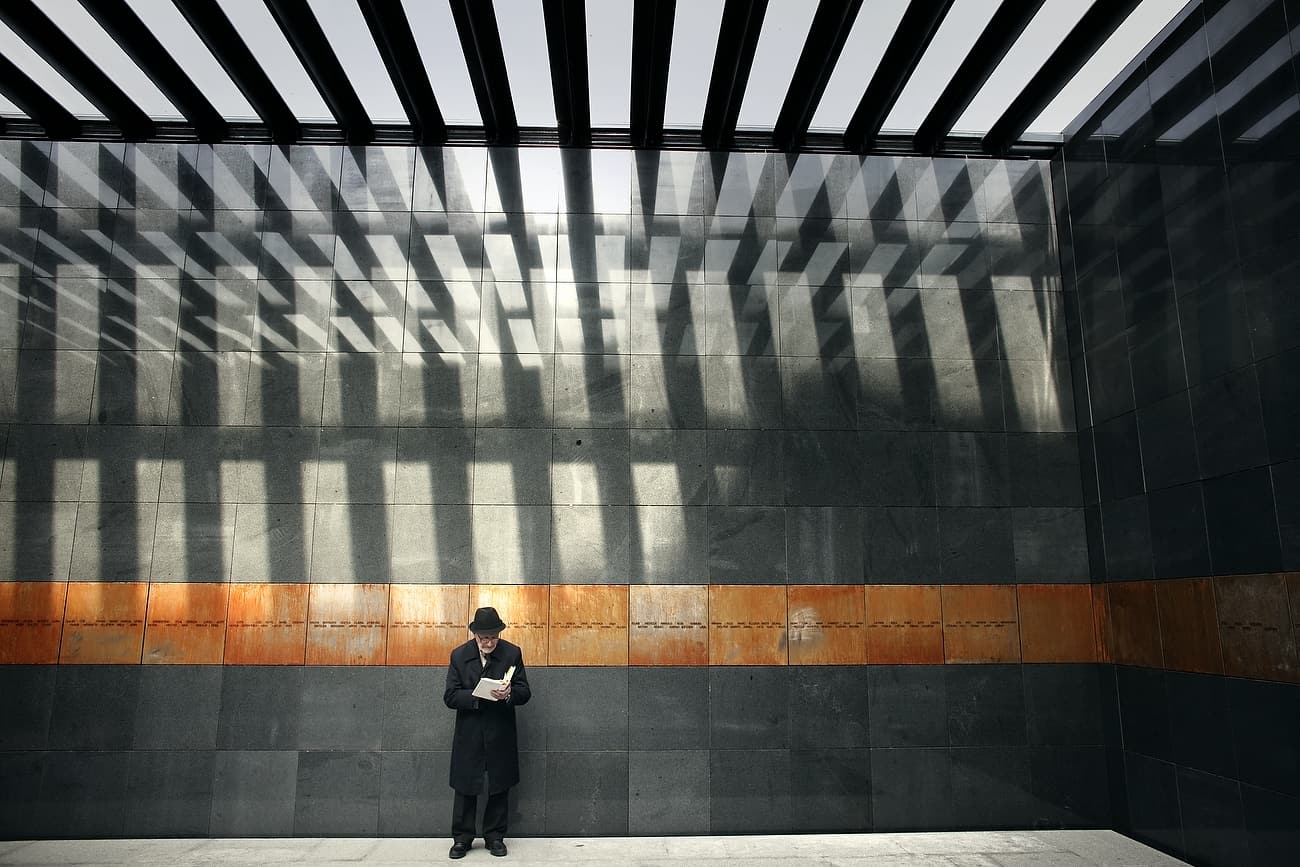

It is to the approximately 250,000 Jews killed in Romania and in the territories it controlled and to the 135,000 killed in northern Transylvania under Hungarian control that I dedicate this documentary. To them and to younger generations of Romanians who only by knowing and respecting the truth will have a genuine future.

The first time I met a survivor of the death trains was in Jassy in 2011, when I was working on a project for a French magazine. I still remember that when he began to tell me about the horrors he endured I burst into tears. I was holding my camera in front of my face to hide my tears.

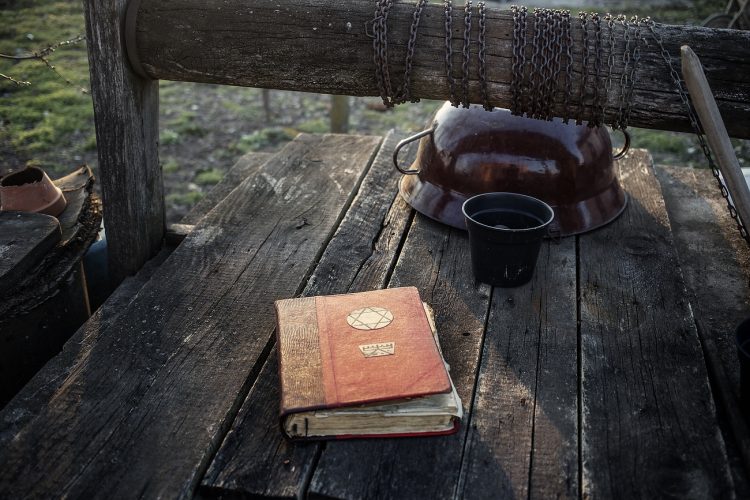

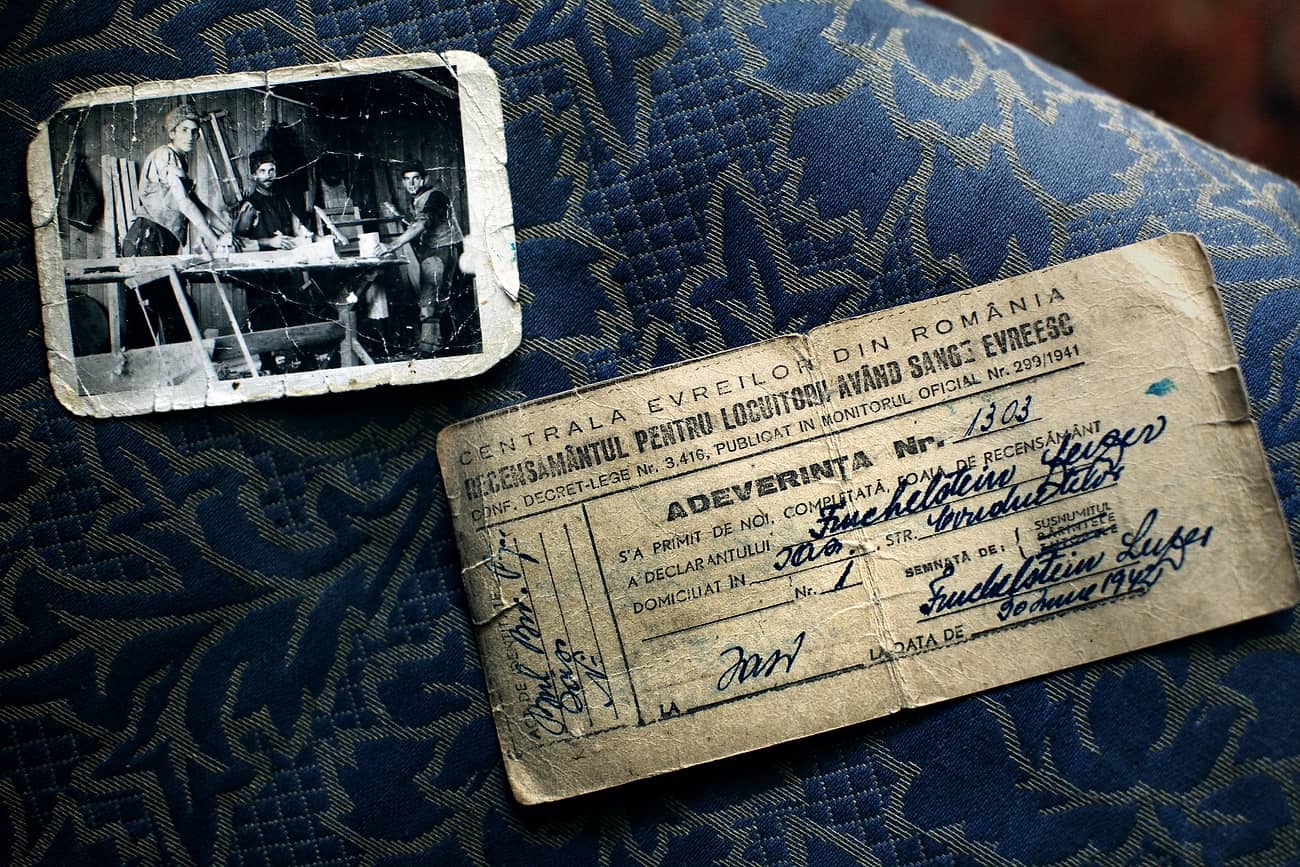

It was not at all easy to see Lazar Finkelstein, a mountain of a man, recounting with tears in his eyes how the Jews were rounded up and taken to the police headquarters. The soldiers were lined up on either side of the entrance and mercilessly beat the Jews with clubs as they went into the courtyard. You had to run as fast as you could, hoping not to get hit. The lucky ones received a blow to the back. Others were hit over the head and fell to the ground lifeless.

But this “warm welcome” was nothing compared with the rain of bullets that fell on the Jews in the courtyard of the police headquarters and nothing compared with the death trains to Podul Iloaiei and Calarasi.

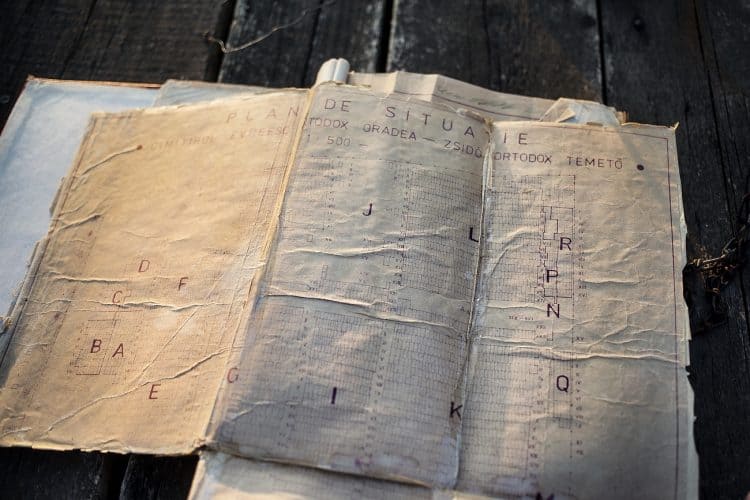

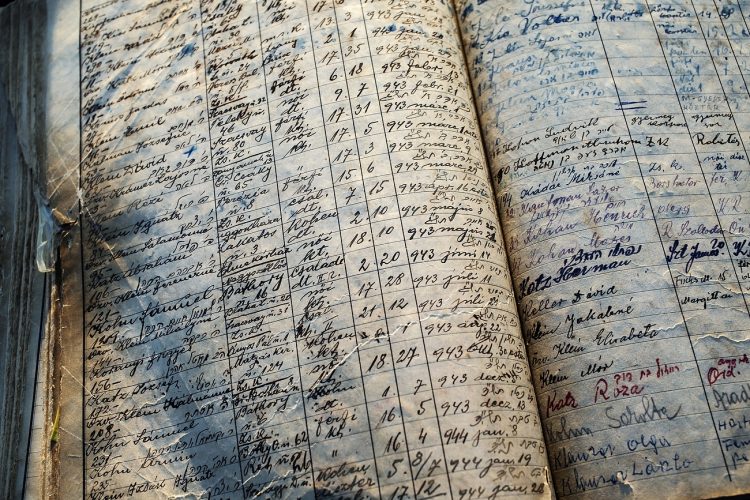

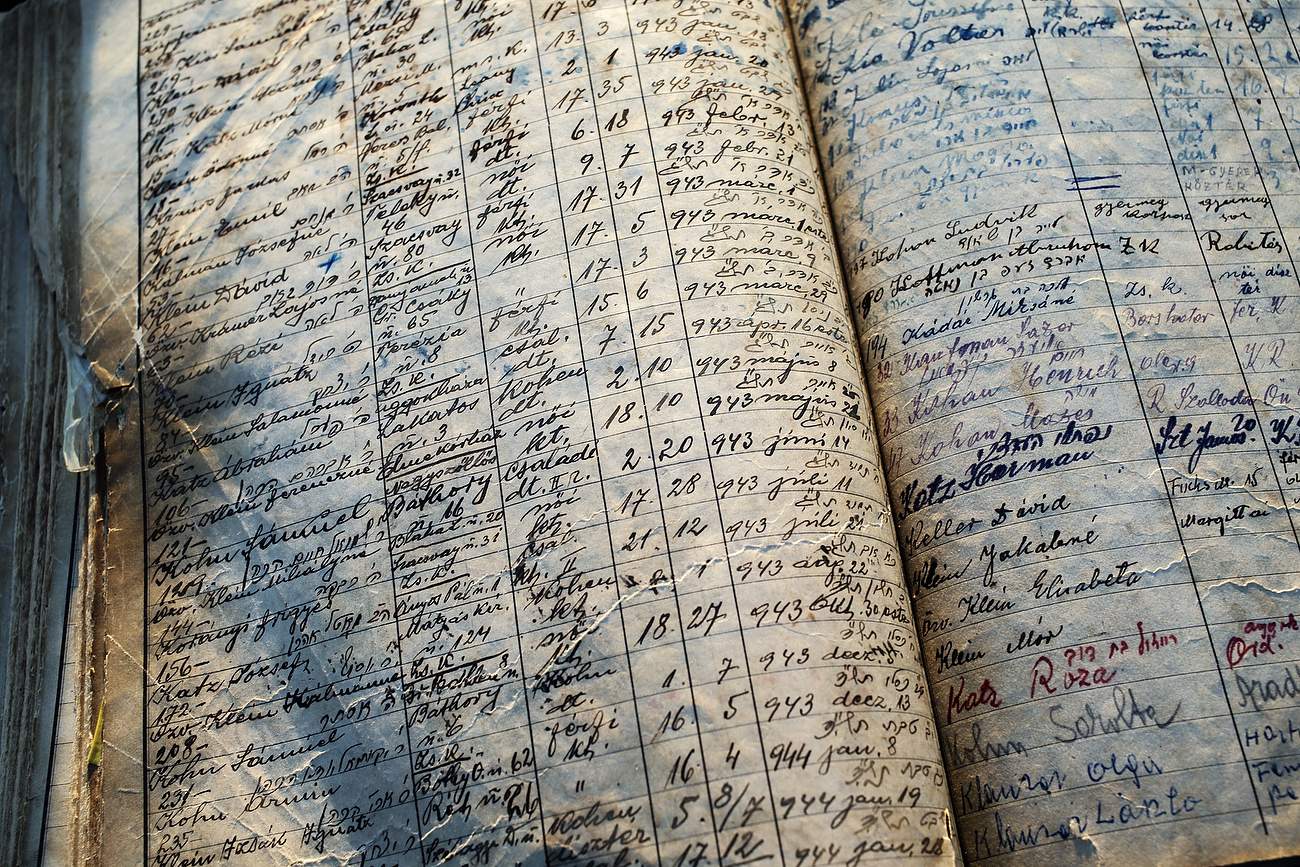

On 29 June, packed into freight cars in conditions worse than for cattle, many of them separated from their families, thousands of Jews lost their lives and were buried in mass graves at Podul Iloaiei and Tîrgu Frumos. The thirty-kilometre journey from Jassy to Podul Iloaiei took more than eight hours. But for the survivors the ordeal was not over. The survivors were forced to bury the dead. Then, they were either deported to Trans-Dniester or to other concentrations camps dotted around the country.

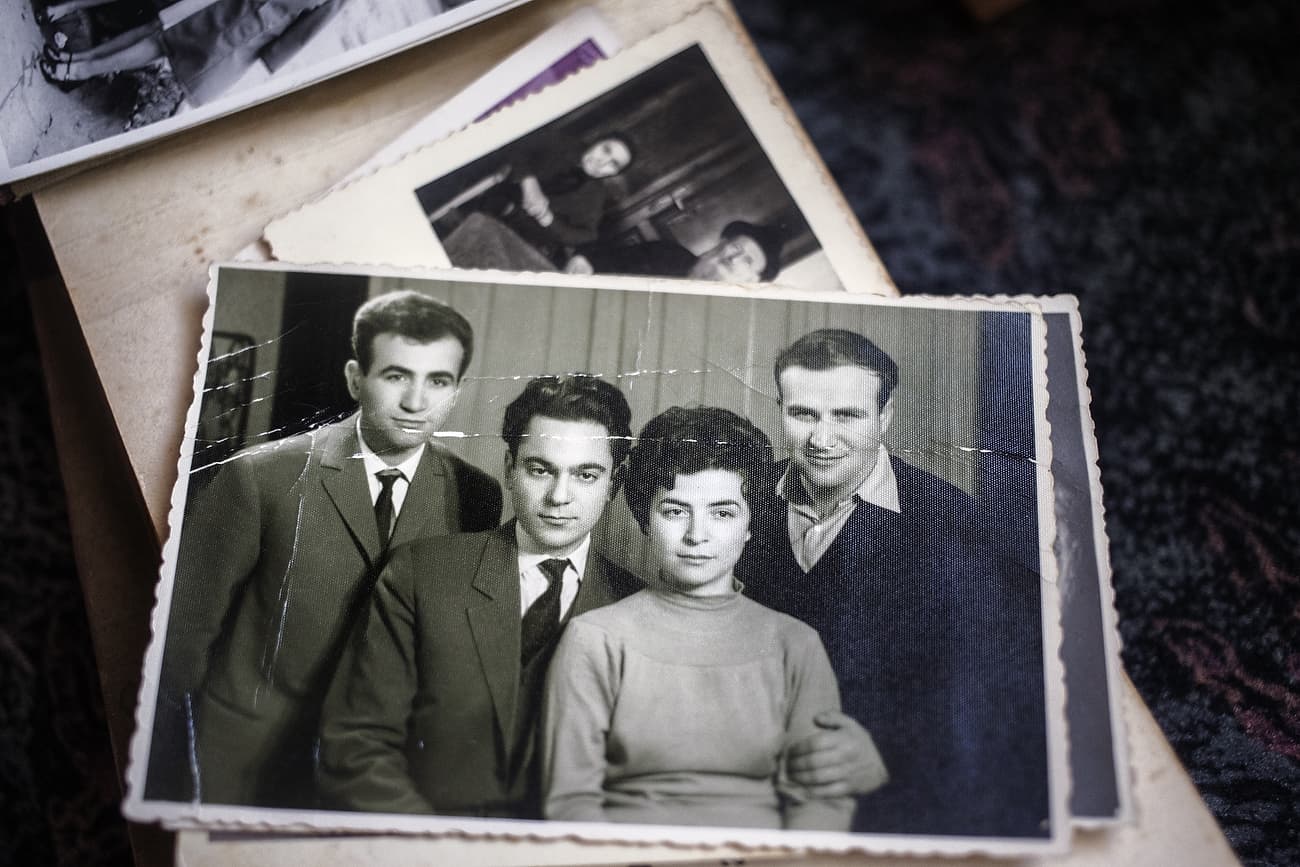

Ever since then, I have wanted to tell the story of those people, on the one hand as a testimony to the atrocities that humankind is capable of committing, and on the other hand as a symbol of the heroism and endurance of human beings.

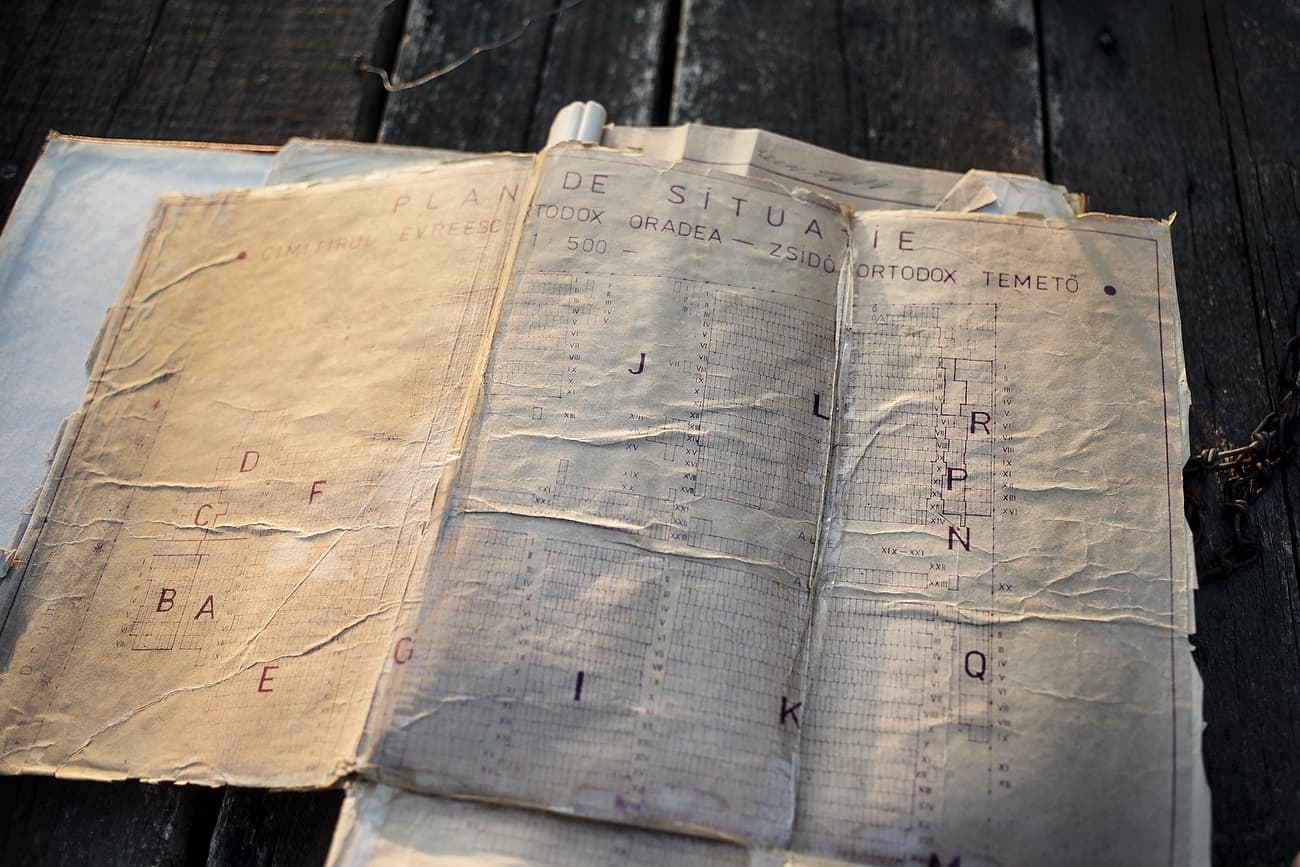

Four years later, in 2015, I resumed work on this documentary. After Jassy came Bucharest and then Oradea.

In Bucharest, I met Miriam Bercovici, a survivor of the Djurin ghetto, in a town between the Dniester and the Bug. As part of the persecution of the Jews, first of all she was forbidden to attend school. And then it was announced that on 11 October 1941 all the Jews in Campulung Moldovenesc were to be deported. ‘Mimi’ was seventeen at the time. On the day before the deportation they were told not to take with them anything more than they could carry. ‘Well-wishing’ neighbours turned up at their door, ready to lay their hands on the belongings of those about to disappear. How nicely they spoke to them until the house remained empty! The next day, as the Jews made their way to the train station, the same ‘well-wishing’ neighbours spat at them and shouted ‘Death to the Yids!’

The journey on the death train made Miriam see how quickly people can shed their humanity in the face of imminent death. In the crowded freight cars, to sit down could mean death by suffocation. The young girls were forced to go to the toilet in full view of the boys they had grown up with. The old and sick were dying all around them and nobody could do anything. On the journey and then in the ghettos the Jews lost their grandparents before their time.